If you’ve just stumbled upon this blog, the first series of posts is an introduction and overview of why and how I created an alternate reality game for my 7th grade English classroom. If you want to know more about that, check it out and tweet me with any questions! I also recommend checking out the guide I co-authored with Paul Darvasi on his blog, as well as his fantastic series on the ARG he created for his 12th grade students.

This will be the first of three entries discussing the mixed media unit I put together for my 9th grade English class that combines Sam Barlow‘s excellent video game Her Story with a series of short stories to study the infamous unreliable narrator.

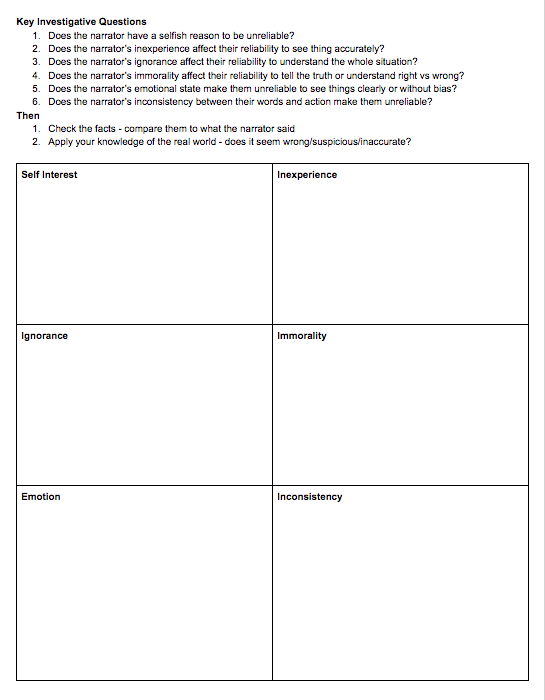

I’ve always been intrigued by an unreliable narrator. As someone who has always been fascinated by games, it makes sense: an unreliable narrator inherently creates a contest between narrator and reader. Not only must the reader evaluate the layers of the story itself but then they must ask if the “facts” of the story are, indeed, even facts. A story as simple as Shirley Jackson’s Charles becomes a delightful literary prank that reminds us that we all tend to believe what we want to believe, even when the uncomfortable truth is staring you right in the face at the dinner table.

Unreliable narrators force us to see the text, down to its DNA. Like Neo in The Matrix, we must learn to see that the mechanisms that hold the fictional world together – inconsistencies, hyperbole, falsehoods, etc. – are no longer merely the instruments of an author’s world building, but challenges and distortions that we must overcome to fully understand the story. We must – by definition – play. In the end, it is a paradoxical effect: we are simultaneously drawn out of the story as we tear it apart like a tinkering engineer, but the narrator’s flaws and even untruthfulness somehow make them more real, more – dare I say – human.

But it wasn’t until reading glowing reviews of the indie hit Her Story that the first ideas for an unreliable narrator unit began to germinate. The Polygon review’s opening had me thinking of English class immediately:

“Her Story has made me obsessed with detail.”

Attention to detail, comparing and contrasting information over the course of a text, nurturing skepticism, constructing an interpretation? A game “[t]hat left me to piece together the story as best I could, filling in the gaps with context and intuition”? That sounds a lot like the skills of close reading I teach for any traditional text. And Her Story turns it into a genuinely fun game? My game based learning instincts smelled a winner.

Super Serial

The Internet age is undoubtedly a voyeuristic one. In fact, humanity has a habit of using its newfound mediums of communication and observation to spy, pry, and snoop almost as soon as we invent it. For better or worse, we are addicted to observing others and devouring the narratives – real or imagined – of their lives. As Dennis Perry says about the Hitchcock classic Rear Window: voyeurism allows us to “relieve ourselves of the burden of examining our own lives”.

I’m not spying, I’m just relieving myself of the burden of examining my own life

Contemporary pop culture sensations like Black Mirror’s White Bear show us the horrific extremes of voyeurism within the realm of science fiction, but it was 2014’s breakout podcast sensation Serial that brought our addiction to true-crime mystery into the national zeitgeist (soon to follow would be the extremely binge-worthy The Jinx and Making a Murderer). In many ways, it was now official. The instant communication, the omnipresence of digital media, and the dark cravings of being near – but safe from – danger all created a potent narrative cocktail.

The potential ethical quandaries of entertainment co-opting real life tragedy aside, it was clear that our inherent urge to solve mysteries – to leave nothing unexplained – could be a powerful intrinsic motivator harnessed to help students build their reasoning, critical thinking, and media literacy skills. Serial quickly became a dramatic focus of classrooms around the world, in addition to becoming the world’s most popular podcast. Her Story, released on June 24, 2015, was perfectly timed.

When I booted up Her Story for the first time, it took only minutes before I was similarly hooked. The faux-CRT screen that encapsulates the story was not only nostalgically amusing to my 90s childhood roots, but its verisimilitude was also incredibly effective at drawing me in. Very quickly, I was deeply immersed into the game. The computer was real, the clips were real, the mystery was real. The murder was real.

So how does Her Story work?

How do you turn this thing on?

Her Story is undoubtedly an unconventional video game, especially compared to the mainstream market of commercial games; there are no points to score, there is no 3D space to explore, there is no (directly controllable) player avatar, and there are no failure conditions that end in virtual death or the dreaded “game over”. At its core, it is an interactive movie, and while many books could (and have) been written what makes a game a “true” game, we will avoid that particular philosophical flame war and use Jane McGonigal‘s definition, which I like for its simplicity:

Her Story checks all of those boxes quite easily.

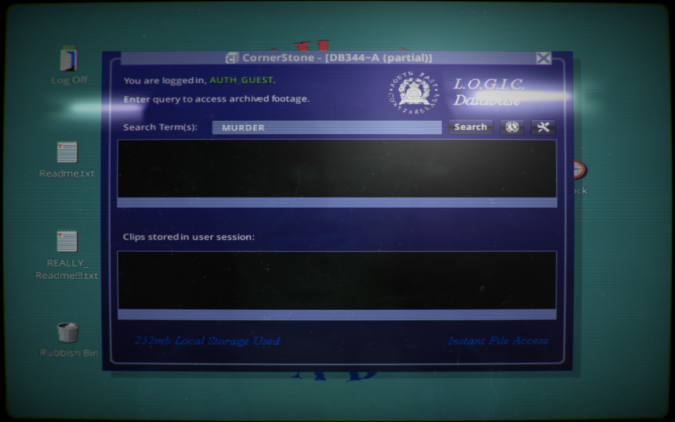

For reference, here’s an annotated screenshot with the major aspects of the game’s interface:

Her Story is built for investigative reading and critical thinking

It took only a few minutes of playing to realize that Her Story was not only a game tangentially applicable to English class curriculums, but that it was in fact a close reading game. The entire user interface and narrative experience is designed for the player to dissect, analyze, and annotate text and video.

The core content of the game is a fragmented video archive of several different interviews, all accessible through the virtual desktop of an ancient PC hidden away in a police department basement. Through a series of events explained in the game’s introductory documents (tucked away on .txt files left on the in-game desktop), the series of interviews with a British woman named Hannah Smith have been fragmented into non-sequential clips of varying length. This jumbled puzzle, however, was hardcoded with subtitles which can be searched in the decrepit, but operational, searchable database program.

When a word or phrase, “murder” for example, is entered into the search box, all clips with that word will be found, but only the first five clips will appear for that search. Here is the game’s central “rule” and “feedback system” – you will have to search precisely with varying words and phrases in order to discover all of the game’s 271 clips. As a result, the narrative is completely non-linear. The player’s curiosity and interpretations determine the exact sequence of the story. The search box provides a nearly infinite broken mirror of narrative routes, both in the exact sequence of discovery but also in the narrative’s inherent Serial-esque ambiguities.

“Guilty” and “kiss” would be likely to turn up this exact clip in top five results. “After” and “felt” less likely, and “the” and “I” would essentially turn up five random clips due to their common use.

The game is well designed to help players organize their exploration of the text. Clips that have not been viewed before are given an “eye” icon to readily indicate that a search has turned up new content. Every clip can be saved to a “favorites” bar underneath for easy access; as the number of important clips grows, the tagging feature becomes more helpful and allows the player search for clips by any tag given to them, as well as any words in the transcript. For the completionists out there, there is also a visual indication of how many un-viewed clips remain.

Hopefully, from this brief overview you can see what I mean when I say Her Story‘s user interface is essentially a close reading program. With its complex narrative, multimedia layers, emphasis on notation and analysis, I was easily convinced this was a video game worthy of being studied in my 9th grade curriculum. In fact, it scored a respectable 5 out of 6 with the National Council of Teachers of English’s 21st Century Literacies.

Develop proficiency and fluency with the tools of technology

Her Story is essentially Google searching and video analysis. Check.

Build intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others so to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought

The game worked even better than I thought in a “hot seat” method (one copy of the game being played with the whole class) – it was one the students’ favorite aspects to play, dissect, and discuss the game collaboratively. Check.

Manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information

The students were at first a bit overwhelmed by the sprawling narrative, but quickly found that the complexity of piecing together the transcript, analyzing the body language of actress Viva Seifert, and exploring the non-linear and ambiguous narrative to be both challenging and exciting. Check.

Create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts.

Design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes.

This is quite literally the game. However, as I’ll discuss in a subsequent post, the students also critiqued and analyzed the game through either a critical review or a “cold case” feature article, which is then published online. Check.

The unreliable narrator, however, also has a newfound relevance in today’s mad media world. “Fake news”, misinformation, disinformation, memes, hoaxes, and pranks are all being shared and transmitted at a rate and volume that is hard to comprehend. Facebook alone has about 510,000 comments posted every minute; Twitter posts range in the hundreds of millions per day. And our students are, on average, spending nine hours a day in that world. It takes only a few minutes of browsing the Internet to realize the world is full of unreliable narrators. Anything that can help our students build the skepticism and analytical skills to parse truth from fiction, fiction from truth and everything in between, seems essential in the informational battleground that has become 21st century media.

With the confidence this was fitting perfectly in a 21st century English curriculum, it was time to put the pieces together. It was time to hit the game based learning lab!

It was time for the students to meet Hannah.

Next time on Getting Unreliable: we find the perfect “levels” of unreliable narrators in short stories, build a note taking apparatus, and find a way to add more choice into the summative writing assignments.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This is an overview of the two writing options from a presentation I gave at the

This is an overview of the two writing options from a presentation I gave at the